Like a rushed, money-grabbing, Hollywood prequel, I’ve waited until my second post to set the scene. To share the series of fortunate events that have led me to write these words in a shipping container in a dusty village ten minutes from the Indian Ocean. This is our first time in Africa. We quit our jobs at the end of November and set off travelling around Europe at the end of December. From volunteering with vegans in the Swiss mountains to being racially abused by Hungarian six-year-olds, it was a blast. We would’ve liked to spend more time on the continent but Brexit.

The three months we spent in Europe were pleasant, relaxed and organised. We knew that at least two of those things would not be true for the next six months of our adventure.

We flew from Budapest to Mombasa via Dubai at the end of March and we weren’t quite sure what to expect. My only preconceptions of Africa come from Colonial Studies, Children in Need, long-distance running and a World Cup fourteen years ago. As the landing gear unfurled over red earth and corrugated iron, I expected swollen babies’ bellies, barefoot football and skeleton men with massive strides running five-minute 5kms.

I’m being facetious, of course, but this is my point.

We’ve long been sold a vision of a congruous continent of similar countries reeling from civil wars, health emergencies and corruption. Other than “Kenya for elephants, Rwanda/Uganda for Gorillas and Mozambique for beaches”, I didn’t know what makes each of these countries distinct from one another.

We’ve been in Kenya for five weeks. We’re in Africa for (at least) five more months. I intend to learn as much as I can about the differences between these nations. Nations created in dusty European administrative buildings, some 150 years ago, by insecure men with low self-esteem and racial hatred mixing with opium in their blood. Railways were built with Indian labour, resources were discovered and syphoned for profit and democratic elections took place post- European withdrawal…but only after we gave them the autographed textbook on autocratic rule.

But anyway, I digress. Here are five things I’ve learned about Kenya so far:

Corruption is actually everywhere - we were scammed in the airport and witnessed a bribe take place within an hour of being in the country. Overstay your visa? There’s a price for that! Stealing land from locals? There’s a price for that! Institutional funnelling of public funds for the private enrichment of a few wealthy leaders? You guessed it, there’s a price for that!

Everything is done on WhatsApp - This one took me by surprise at first. When I say everything is done on WhatsApp, I make no exaggeration. Booking a hotel room? WhatsApp. Getting from A to B? WhatsApp. Booking a four-figure three-day safari with several components? WhatsApp. The app is the beating heart of Kenyan communication and it lurches between extreme efficiency and anxiety-inducing unreliability. For example, I booked an overnight safari with a recommended contact on WhatsApp. He met me for a deposit and spoke about the itinerary. No booking confirmation. No hotel reservation. Just good impressions and trust. I then had to hope he’d turn up at 6am a week later. If he didn’t, if he blocked me and ran, there was nothing I could do. I would’ve lost my deposit. However, thankfully, he was right on time and the entire experience was perfect. It’s ironic, because in a country that is 126th out of 180 on the Corruption Index, you cannot get by without trust here.

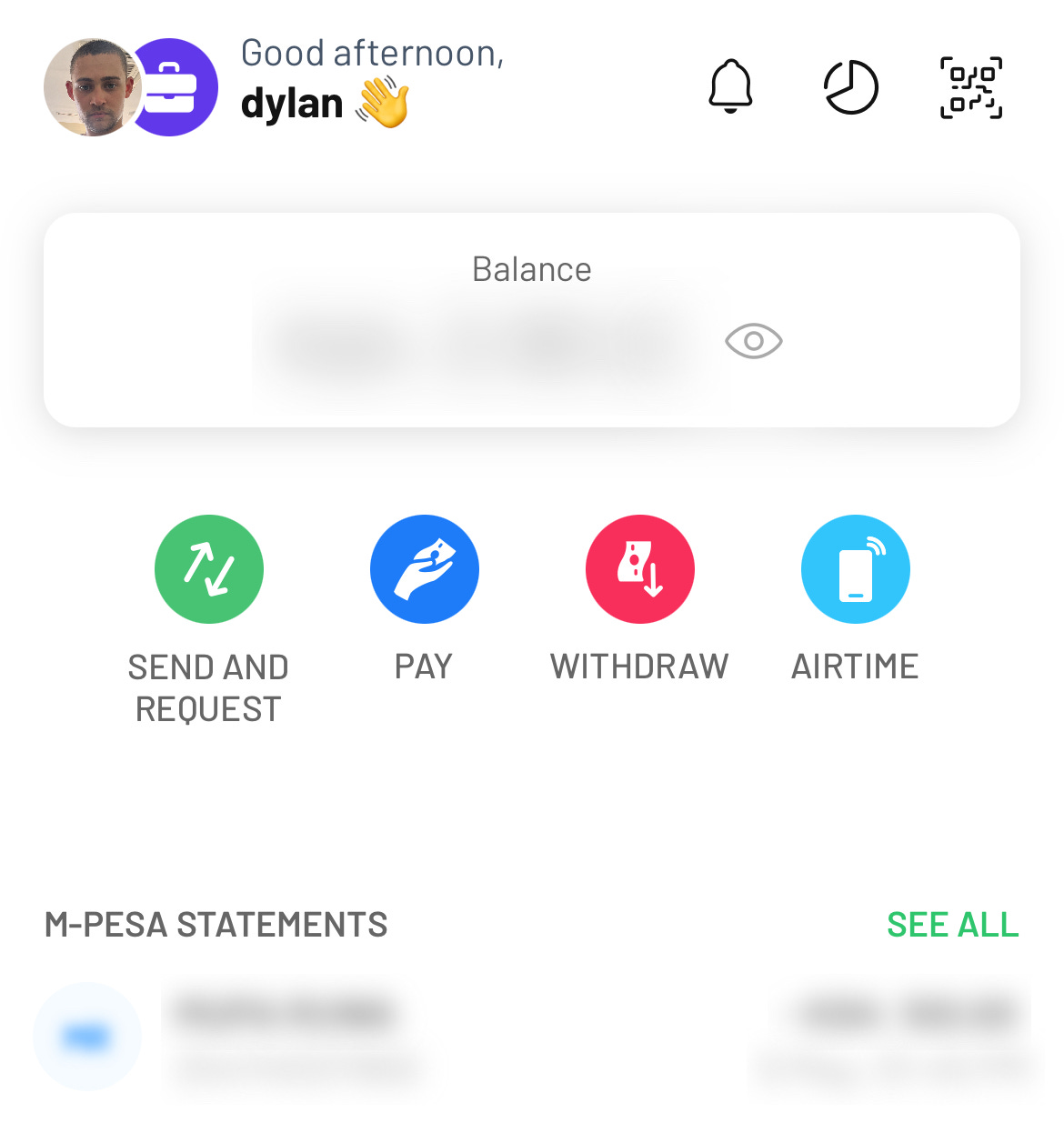

Cash (or M-Pesa) is King - The moment you leave the airport or your hotel, your visa debit, Mastercard or Amex is pretty useless. And if you can use it, prepare for exorbitant transaction fees. When we arrived, we withdrew cash and used that for our food, drink, transport and excursions. But we soon noticed people using M-Pesa. “You don’t have M-Pesa?” they’d ask, with all the attitude of a traveller out-travelling another, less-experienced traveller. But they had a point. M-Pesa is amazing. If you’re in Kenya for more than a couple of weeks, it’s absolutely worth it. Introduced in 2007 (7 years before Apple Pay), M-Pesa essentially meant that anyone with a Safaricom SIM card can have an account which they can use for transactions. No credit card fees, no transaction fees, no bank accounts. All you need is a local SIM and boom, you can get around. From roadside shacks selling beans and chapati to five-star beachfront hotels, everyone accepts M-Pesa. You land in Kenya, you find a Safaricom shop and they’ll do the whole set-up for you. What’s more, you can still use the WhatsApp linked to your UK/US number while you have the local SIM inserted.

Race isn’t black and white - If you’re a white person here, aka mzungu, you are treated very differently than if you were local. Tuk-tuks are more expensive. You will pay more to go on excursions. You might even be served a different menu in a restaurant: one with ‘mzungu prices’. This is part of the game here. Your skin tone suggests a privilege that you are required to pay for. Even if you have never felt that privilege in your life, you pay for it here. There is some hostility here, too. Locals can be suspicious of mzungus. There are those who participate in the tourism industry, and therefore do everything to protect and defend the positive reputation of their people, and then there are those on the outside. Those who are resentful for the preferential treatment experienced by westerners and therefore rally against it (understandably so) with tiny protests of floating scorn and floppy malice, like punches in a dream. Being white here absolutely protects you from some of the worst experiences you can face. Boda (motorbike) drivers will advise you on the safest places to go. They’ll give you their number and act as a personal chauffeur for your trip. You won’t face physical violence or threats from locals because of the protection travellers have at a state level. You see, attacks on westerners, rare as they are, are treated with so much more severity than attacks on locals by locals. So if you can live with the simmering hostility, you’re actually very safe as a westerner in Kenya.

If you don’t drink, you smoke, or chew - My God. People here love to drink. The local drink of choice is Palm Wine. This can be dangerous because it’s made locally. “Made locally” is a euphemism for “could blind or kill you”. Most people drink it without problems, however, well, until the morning after. I’ve also noticed a lot of people drinking Guinness Export. I asked one man, named Salim, why so many people drink it instead of the local lagers. His simple response was “Same price, more alcohol.” This is when I understood. Many of these guys prefer to spend most of their days in a tropical haze. One of my Boda drivers, Paul, described his day to me: wake up, smoke a joint, go to work, chew khat (plant, stimulant), go to bar, drink. It’s a lifestyle that I think many could get behind. Not concerned with the deadlines of next week or month, this lifestyle revolves around the enjoyment of the present moment. If you’re blissed out for 90% of said present moment, there’s not too much to complain about. Especially, when your culture does not revolve around infinite progress and incessant productivity.

If you’d like more of my worldly insights, just pop your email in here.

“Why Human Sushi?” I hear you ask.

Human Sushi

Welcome to my Substack. Long time reader, first-time poster, etc, etc. I’d like to utilise my debut post as an independent writer to write about dreams. Cliché, I know, right? Unlike most, I adore hearing about other people’s dreams. The filler that makes them squirm. The demon dinner lady (intentional Horrid Henry ref.) asking for change that you’ve forg…