The accommodation was quiet. So quiet, in fact, that I could hear my gurgling guts after three portions of poorly cooked train chicken over the past 24 hours.

We weren’t the only ones staying there. The larger room was occupied by two weed-smoking Malawians and their sour-faced Danish girlfriends. The guys asked if we wanted to share a taxi down to the Malawi border but I already knew that their girlfriends wouldn’t be as enthusiastic.

Besides, we wanted to make our way to the border on local buses. We wanted to save some money and finally take the plunge and ride the dala-dala. Also, sharing with them would’ve been at least $20 whereas the local buses, deathtraps as they were, would’ve cost less than $6 between us.

You know when Jennifer Lawrence is asleep in the cryo-chamber in the film ‘Passengers’? Right before Chris Pratt wakes her up. She looks so peaceful, right? That’s how we slept.

No call to prayer.

Nobody blasting Tik-Tok at 5am.

No kids playing games outside our window.

Silence.

It was heaven.

We woke just before breakfast at 8am. Our trip down to the Malawian border and onwards to Mushroom Farm Eco Lodge was supposed to be 5 hours. Light work.

We ate with our host, whose cousin cooked crepes and eggs with a few small bananas. We enjoyed some coffee and conversation before packing up and paying for our night and the breakfast. It was just $4 each.

We piled our luggage, my oversized rucksack and the suitcase we’d grown to despise, into this glorified Little Tike Cozy Coupe and rattled off towards the bus station. I had the same conversation with the tuk-tuk driver that I have with most people here:

“Where are you from?”

“Manchester.”

“Ah! Manchester United.”

“Hmmm, Manchester City.”

“Yes, yes Manchester City!”

“Who do you support?”

“Arsenal.”

“Great team.”

After around fifteen minutes, we arrived at the bus station. I say bus station, but like most African bus stations, it was a car park filled with buses. Before we’d even stopped, a local guy hopped into the front of the Tuk-tuk, dollar signs rolling around his eyes like Scrooge McDuck. Where there are mzungus, there is money… or so he thought. He eyed us like a desperate man looking at last night’s lottery numbers.

“You want to go to Dar es Salaam, yes?”

“Actually, we need to get to the Malawi border.”

He looked disappointed.

“Ah, you go to him.” He pointed at another eager local, looking for passengers for the bus he’d spend the next couple of hours hanging out the side of.

He took Ellie’s suitcase while I haggled on the price in broken Swahili. Saba, Saba. 14k. Less than £4.50.

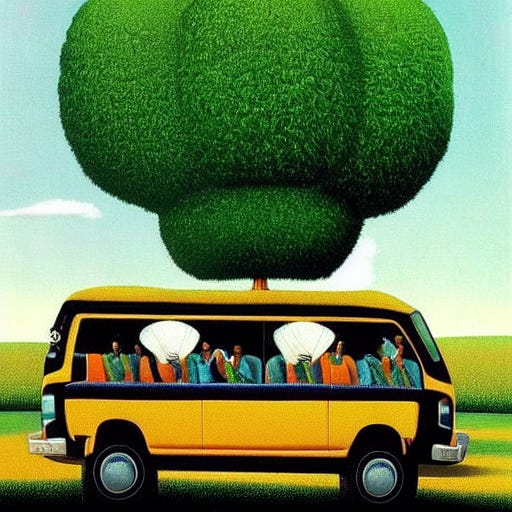

We jumped onto the empty minibus and wondered if it would fill up. Within a few minutes we had our answer. First, three or four women shuffled down with babies strapped to their backs. Then a couple of old men sat around with newspapers and pork-pie hats.

After five minutes of stop-start travel, the bus was full. When I say full, I mean the 21 seats of the 21 seat bus were taken up. That means nothing in Africa.

Between each row of three there were fold out chairs so that people could sit in the aisle. Once they were filled, more people still piled on. They sat on knees, on upturned buckets and when there was literally no more floor space, they stood.

I counted 35 people on the 21 seat minibus. We were the only mzungus, clutching our daypacks to our chest and looking out at the rolling hillsides. We travelled through endless banana plantations and the bus lurched into lay-bys and stopped so that people could grab refreshments from the desperate palms that thrust into the windows offering everything from watches and sunglasses to red onions and tomatoes. I joked to El that you could do your big shop while riding the bus home and this wasn’t much of an exaggeration. We pulled into another car park filled with minibuses after around an hour of driving. We were told that the bus would be turning round and we must get on another one to reach the border.

Travelling through Africa, you have little choice but to trust what you’re told. We took out our luggage, dusty brown from broken sandals after being used as a footrest by those on the back row, and moved to the next bus. With the help of the bus-boy, I wedged El’s suitcase into the boot but there was no space for my 120l rucksack. Instead I had to balance it on the shelf behind the front passenger seat. Ellie was lucky to get a seat next to the driver and I was on an upturned bucket on the floor. Boys in ripped red t-shirts spoke in Swahili and laughed at me. It must have been hilarious to see a mzungu riding the local bus.

The driver chatted loudly on his prison phone drove like a wanted criminal, speeding violently despite carrying twice the recommended number of passengers. After some time, he was stopped at a police checkpoint and an officer boarded the bus. He looked at us for a few seconds and got into an argument with an older man at the back of the minibus. I was desperate to understand what they were saying, convinced that our whiteness was partly responsible for the hold-up. When the man calmed down, the officer turned to us.

“Hello, how are you?” He didn’t smile.

“Good. How are you?” I was polite but plain. I was conscious that I often overtalk in such situations and I was painfully aware that we had an audience of almost 40 passengers.

“I am fine. Passports please.”

El passed me the passports and I passed them to the officer. He flicked through the pages like a bored teenager reading Of Mice and Men.

“Where are you going?” He asked without looking up.

“Livingstonia in Malawi.”

“Where have you been?”

“Mbeya.”

He looked up, handed me the passports, thanked us without looking at us and exited the bus.

No sooner had we come to a halt, the minibus lurched on once more. Conversation and giggling broke out among the passengers and we knew we were the subject. The worst part of the incident was that I was sat at the front of the bus facing everyone. I was on full display, sat on my bucket. All I was missing was a ‘dunce’ hat and I would’ve been the perfect class clown.

We moved on for maybe another forty minutes before stopping at the top of a quiet hill populated with a few mud huts and a row of men lying lazily on their motorbikes.

“BORDER! BORDER! BORDER!” Shouted the bus-boy. He intimated at us to get off. We were confused.

“What do you mean?” I asked quizzically.

He responded with a wave of his hand and the passengers laughed once more. I nodded to El and we got off the bus.

“Where is the border?” I asked. He pointed at the motorbikes as we pulled off El’s suitcase.

As the bus rolled off, the men on the bikes sprung into action. El looked unsure, but we didn’t really have any options. We tied the suitcase to one bike with bungee cords and El placed my rucksack across her lap. We hopped onto the motorbikes and sped towards the border… we hoped.

Within a couple of minutes, two men jumped out of a bush and the bikes slowed down. What felt like a violent ambush was actually a pair of money changers. They asked if we needed Malawian Kawacha in return for whatever Tanzanian shillings we still had. It was perhaps too convenient and I should’ve been more suspicious, but I’m used to strange happenings by now and I acquiesced. As we were changing money, we heard an ear-splitting squeal and looked up to see a pig strapped sideways to the back of a motorbike blistering past. The swine was screaming at the top of its lungs and didn’t stop until it whined out of earshot. We clearly looked stunned.

“Swine,” one of the money changers smiled, continuing to count his cash.

“Fucking hell,” I muttered before doing the same.

We hopped back onto our bikes and within five minutes we were at the border. We paid each driver 5,000 shillings (£1.50) and headed for the one-storey building on the Tanzanian side with money-changers, SIM card touts and taxi drivers in tow. Within a few minutes we were stamped out of the country and began walking to the Malawian side of the border with the same crew in tow.

Hot, flustered and weighed down by luggage, our worst nightmare was realised. One of the wheels on El’s suitcase bent and twisted into the gravel. One of the taxi drivers was quick to help, knowing that his support would necessitate our supporting of him, through typical tips. I tried to carry it myself but three men surrounded us, all desperate to help. We tried to fix the wheel but it was completely broken. We dragged the bastard case to the Malawian side and the SIM card man sat with our luggage while we stamped into the country, visa free at no cost - it wasn’t all bad. The taxi driver still lurked close by and I tried to tell him that we wanted a local bus, hoping to save some money.

“No bus until 4 or 5.” He said bluntly.

It was 12 o’clock.

The rest of our new gang of hopeful dependants concurred. We must jump in a shared car for the three hour journey to Livingstonia.

A confident man in a sun-bleached Manchester United shirt with a peeling Chevrolet badge led us some 200m down the road where a small white hatchback was waiting. We negotiated a price with the driver while simultaneously sorting our Malawian SIM cards and paying tips to the men that helped us with our luggage. He couldn’t take us all the way to Livingstonia but he was happy to take us to within 30 minutes of our destination. We accepted without much choice and moved towards the boot of the car.

“They must go on top”, he said. He took out some rope from his glovebox and we threw both my bag and the suitcase on the roof of the car. He strapped them down and we hopped in. There was already a passenger in the back and a young man with excellent English hopped in the passenger seat in front.

We drove for less than two minutes before the driver - whose name I’d missed my chance to ask - took a right off the main road and into a small village. He stopped and the man in the back climbed out between us. As he moved, I noticed something hairy with a heartbeat squished into the boot behind him.

What the fuck?

He flicked open the boot and two goats, who’d been silent for those two minutes we were in the car, hopped out.

I looked at El.

El looked at me.

We shook our heads in silent befuddlement.

We took down our bags and threw them in the boot where the goats had been.

Within the first hour of the journey, our unnamed driver had picked up and dropped off several passengers while also stopping for black-market fuel at least three times. The car had an occupancy of four but he carried six at all times, squeezing three in the back and sharing the driver’s seat with someone else whenever possible.

The man with excellent English hopped out at his village and a man named ‘Gift’ replaced him. He spoke in chewa with the driver and the driver told him we were headed to Livingstonia. I asked if he could take us directly to our hostel and he agreed after renegotiating the price. Despite this, both men decided that the short road to Livingstonia was impassable, and offered to take us on the longer road, claiming that it was just a short detour.

We should have declined. We should’ve said “leave us at the bottom of the short road and we’ll get motorbikes to the top.” We accepted his offer.

One of the biggest differences about driving on Malawi’s roads compared to other African countries is the sheer number of police stops. They have them everywhere, but here they were literally every five minutes. If they saw the mzungus in the back, they pulled us over instinctively, assuming that we’d paid him handsomely.

The stops were relentless and the passengers sighed every time we approached men or women in their white, tucked-in shirts and peaked caps, wooden makeshift barrier blocking our path.

The journey shouldn’t have been any more than three hours, but after three hours we were still half an hour from the impassable road. He lurched into what seemed like the tenth petrol station and filled up. We were getting suspicious that he might’ve had a leak in his petrol tank, but nobody else seemed to mind. The attendant who filled the car had a name badge that read ‘nervious.’ African names truly are a joy. Gift, Nervious, Goodluck, Gladness, Wangu, Zero, Treati and Mr. Happiness are all names that we’ve encountered on our three and a half months in this surreal continent.

We passed the impassable road and as I glanced at the house-sized boulders scattered up the sheer incline, I understood their reasoning. However, as we edged along the road along Lake Malawi, I followed the only other possible route to our accommodation and it looked like more than a short detour.

We drove on for forty minutes at about 60 km p/h before finally turning right. The road snaked and climbed and it was filled with huge lorries crawling up the side of what seemed like an endless mountain. I got more and more agitated as I realised how slow we were going, how bad the roads were and how far we still had to go. Light was fading and the roads were getting worse. I could sense the rising tension in our so-far-placid driver.

We continued to climb for what felt like forever, before stopping by a group of young men to ask for directions. One of them said he knew exactly where we were going and offered to jump in and show us. We reluctantly agreed. We were now an hour late, the sun had set and we had been sat in this car for five hours.

After several disagreements with our new passenger over directions, dirt track roads that limited us to less than 15 km p/h and now pitch black darkness, we arrived at Mushroom Farm Eco Lodge at 7pm.

A journey which Google Maps assured us would take just over five hours took ten. We were tired, covered in dust and dragged a broken suitcase down this steep hillside to the reception. We couldn’t even see the view.

We sat down to dinner with some of the warmest people we’d met so far, enjoyed a beer and swapped stories and all was forgotten.

And this is what I woke up to at 6am. This, and everything that came before, is why we travel.