Last Monday, I went for an afternoon walk through Astley Park. The drizzle slapped my face like I was standing too close to a car wash and the scent of wet gravel hit like a stoner’s first dose of something stronger. The park was more or less empty, with a few couples ‘getting their steps in’ and the odd elderly dog-walker populating the vast gardens, woodland, and central trail.

Such quietude provided space for a sort of walking meditation on place, home, and the weird sense of peace that such spaces offer. Now, for some context, this park has been a central stage for my adolescence and adulthood. I spent entire summers in the woods as a child, and now walk through the park at least three or four times a week. It has always been a sanctuary from whatever temporal crisis or celebration I’ve experienced.

Getting stoned? Go down Astley.

Job interview tomorrow? Go down Astley.

Walk the dog? Go down Astley.

Dog’s died? Go down Astley.

Some might call it a ‘happy place’, but it’s more than that. It’s a place so strongly linked to my sense of identity that it feels as though there’s a piece of it inside me. I step through the main gates and feel a cult-like sense of belonging that’s independent from anybody else

Most people find their adopted homes among like-minded (or situationally similar) people. Pubs, sports clubs, and walking groups might be examples of this, but their powers of connection come through in the social ties that are forged there. It’s the community that breeds contentment, not necessarily the place where the community gathers. Football teams move stadiums, walking groups alternate routes, and pubs change hands and close down. The rapid rate at which pubs close down is a travesty, but red-nosed men with decades of drink in their faces and livers quickly get used to a new pub, especially if the same locals switch to the same pub.

This seems to prove the point that belonging blossoms through social connection, so why do we feel such powers of belonging in our parks? I think the answers are idiosyncratic, so this is going to read as more of a personal essay - a love letter, so to speak - on Astley Park, rather than a one-size-fits-all declaration on what makes all parks peaceful. I might walk through your local park and notice the dog shit on the paths and swings wrapped around frames. You might see burgeoning tulips and octogenarian couples on the bowling green. There’s beauty to all of our shared spaces, if only we take the time to appreciate it.

In fact, maybe that’s the point. Between birthday parties and work and nights out and work and going shopping and work and dying and work, we don’t have all that much time to explore new places. We tick off Wainwrights and admire beauty spots, but once they’re done, they’re done. We like to think that we’re unique snowflakes falling upwards, collecting experiences on our way to a Nirvana-that-never-comes. But in reality, we’re stamp collectors, Pokémon hunters, crisp packet hoarders. We seek out variations of the same thing so that we can say we’ve done it. The more things we do, the more things we can talk about. The more things we can talk about, the more interesting we are.

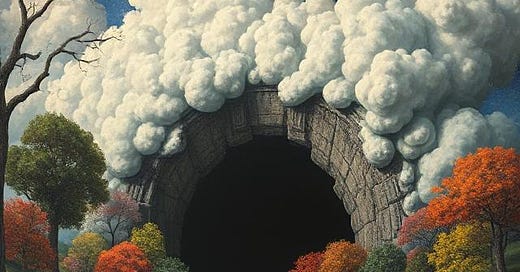

But the thing is with parks, and I want you to think about your local park here, is that we walk through them again and again. We walk through them when we’re happy. We walk through them when we want to die. We walk through them in all seasons and weather conditions. This repetition opens up the space to notice things, and when we notice things, we feel a connection to the present moment. I’m not writing anything that you don’t already know, but I’m trying to make sense of a feeling I’ve never really understood, only felt. So, when I look at the trees in Astley Park, I don’t just see them in the present moment. I see their trembling, naked branches of winter, I see their precariously perched nests in spring, and I see their shimmering emerald leaves in the summer. There’s an appreciation of everything that the park has ever been and everything it ever could be, coupled with the calm and peace of the present moment.

Time might also come into play here. The first signs of human habitation in Astley Park come from around 1400 BC, in the form of burial urns. The first version of Astley Hall was built in 1577, around the same time Shakespeare probably began masturbating. The park began to take the shape we recognise today around 325 years ago, with gardens, woodland, and the hall that we all know and love. The idea that Astley Park has stood in its current form for several lifetimes and will probably remain the same for several more soothes me.

Its constancy invokes the same sense of peace experienced when contemplating supermassive black holes or the syncope-inducing scale of our universe. If something as tiny as my local park can stimulate such wonder, then do we really need to dwell on the scale of infinity, or our rapid acceleration into adulthood, old age, and inevitable death? Probably not.

Before writing this, my intention was to talk about the specifics of the park, adolescent memories, and how it’s been a saviour for me in recent months (more specifically, watching the regulars on the bowling green). Unsurprisingly though, it’s morphed into a rambling meditation on time, place, and decay.

If you need me, you know where I’ll be.